Introduction

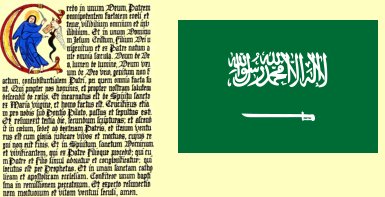

It is said that recitation of the Islamic “creed” known as the shahadah is all that is required for a person to convert to Islam. “Shahada” comes from a word meaning “to know and believe without suspicion, as if witnessed, testification.” The shahadah affirms the following:

“There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is his prophet.”

Now it may seem evident that no Christian could possibly become a Muslim given this criterion. But perhaps a Christian could in good conscience affirm this statement.

The Meaning of Islam’s Shahadah

There are really only two affirmations being made, and I think that given a certain understanding of the shahadah, a Christian could easily affirm it.

“No God but Allah”

In Arabic, the Shahadah reads as follows: “lā ʾilāha ʾillà l-Lāh, Muḥammadur rasūlu l-Lāh”. Note the distinction between “ʾilāha” and “ʾillà l-Lāh”. As many translators note, the word “Allah” is just the Arabic word for “God.” As with Hebrew, there is a generic word for “god(s)” (e.g., “elohim”) and there are also personal names for God (e.g., “Yahweh”). Thus, the shahadah could be translated “There is no god but God.” In other words, there is only one true God. Christians would obviously have no problem affirming that there is only one true God, even if we do not generally speak of this God in Arabic (“Allah”). So, the first part of the shahadah should pose no problem for a Christian.

“Muhammad is his Prophet”

Affirming that Muhammad is the prophet of God certainly seems like a line which a Christian cannot cross, but upon closer inspection it is not nearly that big of a deal. In Arabic, what is being affirmed of Muhammad is that he is God’s “rasūlu.” This word simply means “messenger.” Now, anyone who speaks for God, or who simply conveys a message from God, could be considered “a messenger of God.” As it turns out, in the Quran, Muhammad not only affirms that the Christian Bible is true, he even affirms some biblical truths (examples). Thus, at least in these instances, Muhammad could be considered a messenger of God, for he correctly passed on a message that was from God. So the second part of the shahadah is also fine for Christians to affirm.

Of course, no Muslim would consider such an affirmation of the shahadah in the manner suggested above. “No god but Allah” means that the particular deity of Islam is the only true deity (and is most definitely not the Christian Trinity, i.e., shirk). And to affirm that “Muhammad is Allah’s prophet” is not to simply affirm some abstract sense in which Muhhamad happened to get a few quotes right. Rather it is to believe that Muhhamad was Allah’s special revealer – the revealer of Islam itself – and the last of the prophets. How do I know this? Because that is what Islam teaches – and it’s their shahadah. Therefore, even if I could, in my mind, affirm the shahadah by mentally overwriting its real meaning with my personal understandings, I would still not be a Muslim (good or otherwise).

In fact, Muslims saw this possibility and took steps to keep someone from doing such a thing. Islamic scholars have come up with necessary requirements for a true affirmation of the shahadah including:

- Knowledge of the meaning of the Shahadah, its negation and affirmation.

- Certainty – perfect knowledge of it that counteracts suspicion and doubt.

- Sincerity which negates shirk.

- Truthfulness that permits neither falsehood nor hypocrisy.

- To believe in the Prophet and in whatever he said and conveyed in his message as the seal of the prophets.

- To obey him in whatever he commanded.

That changes things a bit doesn’t it?

The Meaning of Christianity’s Creeds

Christianity has its own creeds to determine one’s faithfulness to its teachings. The primary creed is the Nicene Creed, developed over the first few centuries of the Church’s history and written, developed, and finalized over a 55 year period beginning with the Nicene Council in A.D. 325. In A.D. 381 the Council of Constantinople, the creed was expanded and finalized. Historically, the Nicene Creed was what the faithful in the Church recited in order to affirm their orthodoxy. Prior to entering the Church as members, however, came baptism and with it the requirement to affirm the Apostle’s Creed. It’s nascent form can be seen in the Interrogatory Creed of Hippolytus from A.D. 215 (used to question baptismal candidates), but its current form is found in the mid-6th Century.

Now, I affirm both of these creeds. Thus, it seems, I can be a good Christian. But what if, when “affirming” these creeds, I am really making the same play that I did above with the shahadah? No good, right? Although this might seem obvious, my concern in this post is to point out that while most Christians would rightfully think it ridiculous to say I could be a good Muslim with my distorted understanding of the shahadah, it seems that some Christians have no problem with Christians distorting the meaning of the creeds.

I know Christians, for example, who drop out parts of creeds and even suggest that parts be taken out because they do not personally find them to be true. Popular Christian scholars like John Piper and Wayne Grudem fall into this category. They do not believe that “Jesus descended to hell” as affirmed in the Apostle’s Creed. In another example, the popular scholar and apologist William Lane Craig denies creedal orthodoxy concerning monothelitism. For many of these Christians, the reason they are comfortable denying what the orthodox creeds affirm is that they take the principle of sola Scriptura (“the Bible alone”) to mean not simply that the Bible is the highest authority, but that it is the only authority – and thus, one’s understanding of the Bible can override what is said in a creed.

Problems with this understanding have been raised elsewhere, but for purposes of this post I want to point out that redefining what the creeds say or mean may come from the same errors made when interpreting the Bible itself (a practice no Christian should allow – in theory, if not in practice). If the historical understanding of biblical passages is up for grabs, then so is the interpretation of the Bible. To deny the original meaning of the original writings in favor of one’s contrary beliefs simply because the words used could support another understanding is how cults flourish. When one does not wish to affirm orthodox creedal teachings is to mentally redefine the creeds in order to bring them into conformity with one’s own thinking (this popular apologetics page is a good example).

So, for example:

- “Baptism for the forgiveness of sins” has been said to refer to Holy Spirit baptism instead of water.

- “One . . . Catholic” is taken to mean the invisible / abstract collection of all believers instead of an identifiable, existing group.

- “Apostolic” is said to mean agreement with apostolic teaching (which, of course, just happens to be whatever a given Christian believes) instead of a Church with an objective, historical connection to the Apostles.

Now, these may be true doctrines, but it is pretty clear that they are not what the Church meant when the creed was composed (as shown in the collection of commentaries in this excellent series). So why do some Christians feel free to mentally redefine what the Church meant by its own words? I think it has to do with the above misunderstanding and/or misapplication of sola Scriptura.

When the text is focused upon to the exclusion of all other contexts (historical / theological / etc.), it is easier to think it is capable of multiple meanings. But again, no other types of writing are usually treated in this way. If one thinks it is legitimate to treat the Bible (the only authoritative, inspired, inerrant, infallible, source of doctrine) as just a collection of words that can mean anything that can possibly be born by their dictionary definitions, imagine what havoc one could wreck on the creeds!

Conclusion

One who does not legitimately affirm the Islamic shahdah cannot be an orthodox Muslim, and neither can one who does not legitimately affirm the creeds of Christianity be an orthodox Christian – at least on the creedal criterion. Of course, one may challenge this historic understanding of Christian orthodoxy (here’s one attempt), but it seems dishonest to affirm creeds that one does not really believe simply because it is logically possible to mentally redefine the terms of the creed in ways that better comport with one’s contrary beliefs.

If it is not legitimate to practice private reinterpretation with a one-line Islamic affirmation, then all the more strongly it is illegitimate to do so with Christianity’s Bible or its creeds.